written by Yulia Protas (international volunteer at KAH)

My first visit to the Rukla camp for the most vulnerable asylum seeking migrants, which is located in the district of Jonava, was with Asta, an educator and curator from Kaunas Artists’ House. We held a creative activity for the young refugees, who were living in the reception center for around 9 months by then. Before visiting the camp, Asta briefed me about the town of Rukla and the camp itself, so I knew in advance that the place was not exactly a friendly looking residential area. On our way to the Rukla refugee camp we had to overcome one barrier after the other: a narrow bumpy road, a bridge under construction, traffic jams, military cars and facilities, barbed wire fences all along the way, a gate, a checkpoint, another gate.

By the time we reached the refugee camp, I was frustrated by so many questions flashing in my mind: “Are the people staying in Rukla dangerous? Why does the government put so much effort into isolating refugees? Haven’t those people suffered enough already to stay in the camp? How long will the refugees stay there? Will it ever be possible for them to reintegrate into the world on the other side of the fence?” The cheerful greetings of a camp’s worker helped me to pull myself together.

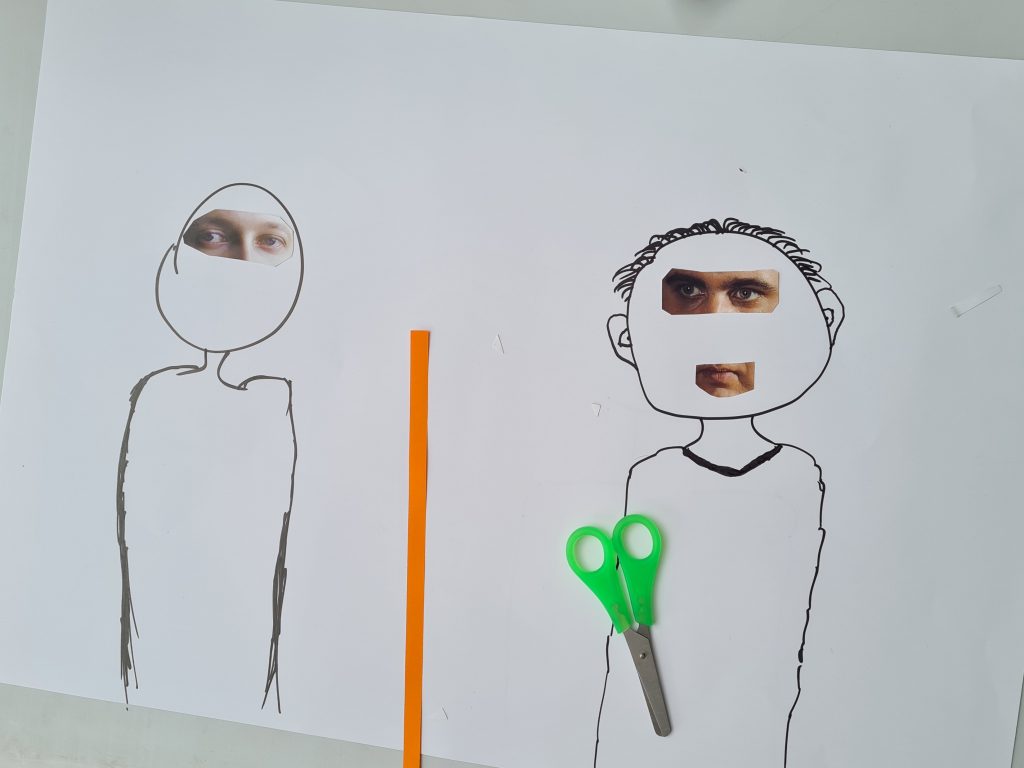

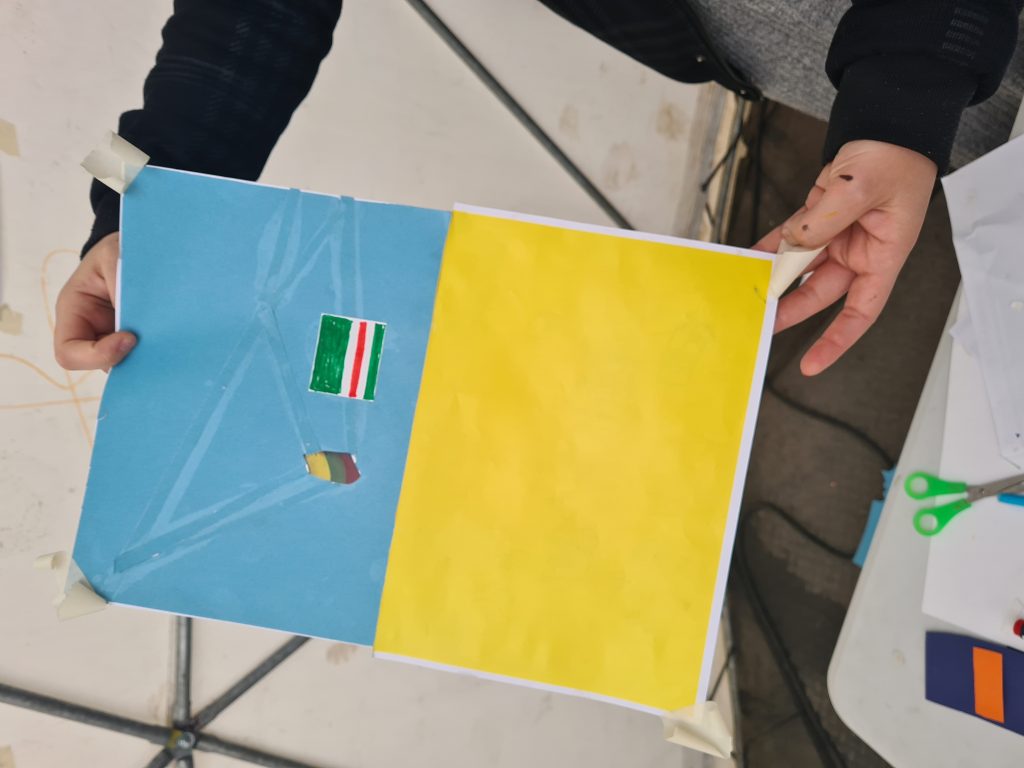

The activity was held in a tent, surrounded by tiny shipping container «houses», where some of the asylum seekers live. Asta’s idea was to suggest the youngsters to make their own portraits as collages of their dreams, thoughts, expectations. When people started to gather for the event, I was confused by the expressions on their faces: it was a mixture of curiosity and boredom, friendliness and distrust, enthusiasm and exhaustion, hope and despair. It took a while to explain the goal of the activity and involve young people to participate. By using a mixture of English, Lithuanian, Russian or just with the help of gestures we found a way to communicate. We smiled to each other, we listened to each other, we wanted to understand each other. We tried to pretend for a moment that military cars, barbed wire fences, gates, check points, and container houses didn’t exist.

After the workshop, we made an exhibition of all the posters made by the refugees in the tent. Each of the posters had a story to tell: a story of a girl, who liked music; a story of a boy, who dreamed about freedom and justice; a story of a young mother and a father, illustrated by their son, a story of a young man, who loved nature. There were deep, beautiful, sad, funny, heartbreaking, sincere, naive stories of the children, teenagers and young people.

Now, when I think about people living in refugee camps, I often feel devastated by my own helplessness: no one can anticipate when and how this temporary period of their lives will finish. Refugees cannot go back, because some of them lost their homes and families, they cannot plan their future, because the court is in charge of it. By being physically limited in camps, refugees are also stuck in a period of the recurrent present, when every day looks exactly like the day before. We, the people from the other side of the barbed wire fence, cannot promise anything to the asylum seekers. But we must take care of them, we must destroy all the barriers imposed between us and find a way to understand and accept each other. Because we cannot really afford to be careless and ignorant anymore.